Irish mythology is among the most vivid and enduring mythic traditions in Europe, comprising a wealth of stories that date back to pre-Christian times. These tales—from the Tuatha Dé Danann to the epic heroics of Cú Chulainn—form the backbone of Irish culture and collective memory. The mythology is organized into four major cycles: the Mythological Cycle, the Ulster Cycle, the Fenian Cycle, and the Historical Cycle, also known as the Cycle of the Kings. These cycles have been preserved in a variety of manuscripts and oral traditions, with many being transcribed by medieval scribes and monks.

To understand these rich mythological traditions, we must delve into the manuscripts and oral traditions that are the primary sources of these myths. We will explore the key documents that have preserved Irish mythology, the scribes who wrote them, and the cultural environment that produced these remarkable stories. This exploration provides insight not only into the tales themselves but also into the Ireland of the past—a land shaped by oral culture, monastic scholarship, and a blend of pagan and Christian belief systems.

Oral Tradition: The Roots of Irish Mythology

Before these stories were committed to writing, Irish mythology existed as an oral tradition, passed down through the centuries by bards, storytellers, and poets known as filí. In ancient Ireland, the filí were highly regarded figures who preserved history, lore, genealogies, and myths. They trained for many years in the art of memorization and oral composition, committing vast amounts of material to memory and perfecting the poetic forms that made these stories captivating to listeners.

The filí held an important social role, with status almost equal to that of the nobility. They acted as historians, keepers of genealogies, and arbiters of cultural memory. They were believed to have divine inspiration, which connected them to a deeper truth and a sacred duty to safeguard and retell the stories of their people. As such, their position allowed for an oral continuity of stories, ensuring that the mythologies remained central to the collective identity of the Irish people.

This oral transmission meant that stories evolved over time, with regional variations and the personal style of individual storytellers influencing their retelling. This flexibility gave rise to numerous versions of a given story, with each version tailored to the audience’s context, ensuring relevance and entertainment value. By the time the stories were finally written down, they had been shaped and reshaped by centuries of oral performance, making them dynamic artifacts of cultural identity.

The oral roots of Irish mythology left an indelible mark on the stories that were eventually written down. The narrative techniques used—such as repetition, vivid imagery, and episodic structures—reflect their oral heritage. These features were essential to help listeners remember the sequence of events and to emphasize key moments. The written texts that capture these myths retain these stylistic hallmarks, providing a window into a past when storytelling was not merely entertainment but also an act of cultural preservation.

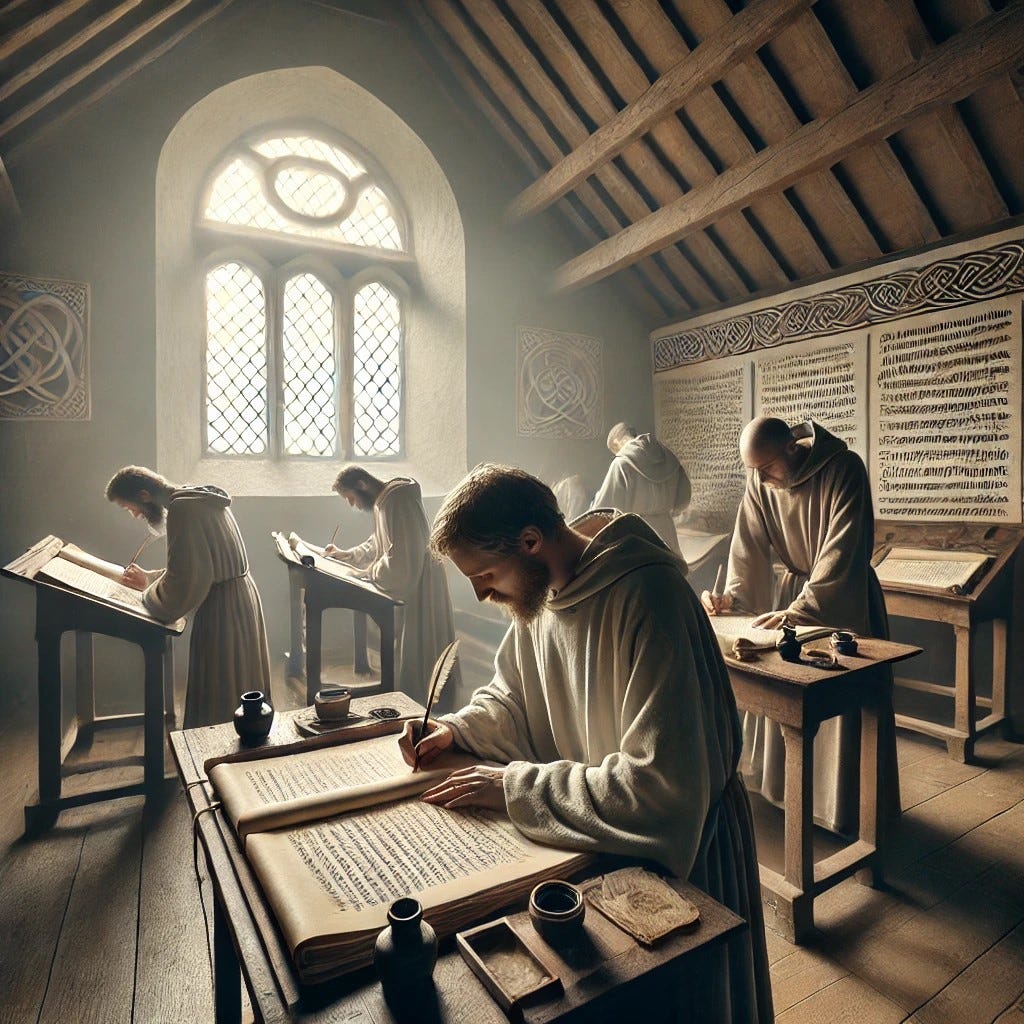

The Manuscripts: Medieval Preservation of Mythology

The primary written sources of Irish mythology come from manuscripts produced during the medieval period, mainly between the 11th and 16th centuries. The most significant of these manuscripts were produced in monastic scriptoria by scribes who sought to preserve Ireland’s cultural heritage even as the island underwent Christianization. The fusion of pagan and Christian elements in these manuscripts reveals the complexity of Ireland’s cultural transformation during this period. This blending allowed the scribes to navigate between the two worlds—honoring Ireland's deep pagan past while embracing their Christian present.

The Lebor na hUidre (The Book of the Dun Cow)

Date and Origins: The Lebor na hUidre, or Book of the Dun Cow, is one of the oldest surviving manuscripts of Irish literature. It is thought to have been compiled around 1100 CE and is named after the tradition that it was written on the skin of a famous cow belonging to Saint Ciarán of Clonmacnoise. The manuscript is believed to have been produced at the monastery of Clonmacnoise, a major center of learning in medieval Ireland.

Content: The manuscript contains some of the earliest versions of tales from the Ulster Cycle, including Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), along with other important stories such as The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel and The Vision of MacConglinne. The Book of the Dun Cow presents an invaluable glimpse into the heroic culture of Ulster. It also preserves early Christian texts, thereby providing evidence of how the clerical establishment was able to maintain and reinterpret pre-Christian traditions.

The Scribes and Their Challenges: The Book of the Dun Cow appears to have been the work of multiple scribes, and the surviving text contains several annotations and marginalia that indicate the concerns and interpretations of its writers. These scribes, likely monks, faced the delicate task of balancing the recording of pagan mythologies with the expectations of a Christian worldview. Some scribes would include marginal comments to provide a Christian perspective on the actions of characters, casting certain pagan heroes in a moral or ethical light compatible with Christian teachings.

This complex process of transcription and editorial commentary speaks to the ambiguous relationship between the Irish Church and the country’s pagan past. The scribes understood the cultural importance of these stories and sought to ensure their survival, even if that meant interpreting them through a Christian lens. Despite this reinterpretation, the essential character and vitality of these ancient myths remained intact.

The Book of Leinster

Date and Origins: The Book of Leinster, compiled around 1160 CE, is one of the most comprehensive sources of Irish mythology, containing an extensive collection of stories from various cycles. It was likely produced at the monastery of Terryglass by the scribe Áed Ua Crimthainn, who was both a scholar and a cleric.

Content: The Book of Leinster is particularly valuable because it preserves a more complete version of The Táin Bó Cúailnge, as well as numerous other stories from the Ulster Cycle and Mythological Cycle. In addition to mythological tales, it contains poems, genealogies, and historical texts, providing a broad view of Irish culture and history. The breadth of the manuscript suggests a desire to create a compendium of knowledge, capturing not only the myths but also the historical and social context of Ireland.

Áed Ua Crimthainn and His Work: Áed Ua Crimthainn was the principal scribe of the Book of Leinster, and his role was instrumental in shaping the way Irish mythology has been preserved. The manuscript demonstrates a blend of Christian learning and a deep appreciation for the pagan past, as Ua Crimthainn carefully transcribed the ancient stories while ensuring that they were preserved within the context of the Christian worldview that was dominant in his time.

His dedication to preserving these tales indicates that there was a recognition of their cultural significance, even among the Christian clergy. By recording genealogies, heroic sagas, and oral traditions, Ua Crimthainn played a pivotal role in keeping alive a cultural memory that might otherwise have been lost. His meticulous work provides us with a relatively complete image of Irish mythological traditions at a time when oral storytelling was beginning to wane in prominence.

The Yellow Book of Lecan and the Great Book of Lecan

Dates and Origins: Both the Yellow Book of Lecan and the Great Book of Lecan were compiled in the 14th and 15th centuries, respectively. These manuscripts were produced by the Mac Firbhisigh family of scribes, who were renowned for their dedication to preserving Irish history and literature.

Content: The Yellow Book of Lecan contains versions of tales from the Ulster Cycle, the Fenian Cycle, and the Mythological Cycle. It also includes portions of Táin Bó Cúailnge, as well as stories about Finn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna from the Fenian Cycle. The Great Book of Lecan is similar in its scope, with a focus on genealogies, myths, and historical lore. These books are significant as they served as a repository for a wide array of cultural material, preserving not only mythological narratives but also records of law, custom, and historical events.

The Mac Firbhisigh Family: The Mac Firbhisigh family were professional historians and scribes, part of a learned class that was devoted to maintaining Ireland's literary heritage. Their work in producing the Yellow Book of Lecan and the Great Book of Lecan reflects their commitment to preserving both the pagan and Christian elements of Irish culture. The manuscripts they compiled represent a concerted effort to maintain the integrity of the oral tradition while adapting it for a written audience.

In particular, the Mac Firbhisigh scribes contributed to a sense of Irish identity that extended beyond the political upheavals of the period. Their work ensured that the cultural memory of pre-Christian Ireland was not lost, even as the Gaelic order faced increasing challenges from Anglo-Norman influences. The manuscripts they produced continue to be invaluable sources for understanding the mythic landscape of Ireland and the cultural values embedded within it.

The Book of Ballymote

Date and Origins: The Book of Ballymote was compiled around 1390 CE by scribes in County Sligo. It is named after the castle of Ballymote, where it was produced. The manuscript was created during a time when Gaelic culture faced increasing pressure from Norman and English influences, making the preservation of Irish mythology and history even more crucial.

Content: The Book of Ballymote contains an extensive array of materials, including mythological tales, genealogies, and historical texts. It also includes a version of the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of Invasions), which is a mythologized account of the history of Ireland from its creation to the arrival of the Gaels. This manuscript demonstrates the synthesis of myth, history, and legend that characterizes much of Irish literature. The inclusion of both mythological and historical materials reflects an effort to construct a cohesive narrative of Ireland’s past that combined the divine, heroic, and human elements.

The Role of the Scribes: The scribes of the Book of Ballymote were part of a tradition that sought to compile and preserve the totality of Irish knowledge, including mythology, history, and law. Their work is characterized by a meticulous attention to detail, and the manuscript is richly illustrated, reflecting the care and reverence with which they approached their task. The Book of Ballymote was more than just a collection of stories—it was an effort to affirm Irish cultural identity during a period of growing political uncertainty.

The Interplay Between Pagan and Christian Elements

The preservation of Irish mythology in these medieval manuscripts is marked by a complex interplay between the pagan past and the Christian present. The monks and scribes who transcribed the myths were working in a Christian context, yet they clearly recognized the cultural value of the stories they were recording. This dual perspective is evident in the texts themselves, where Christian commentary and moralizing passages are often inserted alongside the pagan narratives.

For example, in the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the story of Ireland’s mythical invasions is presented as part of a divine plan, with the Christian God guiding the events that led to the settlement of the island. Similarly, in The Táin Bó Cúailnge, the scribes occasionally added references to Christian virtues or emphasized the moral failings of certain characters in ways that reflect Christian ethical concerns.

This blending of traditions allowed the scribes to preserve the rich cultural heritage of pre-Christian Ireland while framing it within a worldview that was acceptable to the church. As a result, the manuscripts that preserve Irish mythology are not simply transcriptions of ancient stories—they are reinterpretations that reflect the cultural dynamics of medieval Ireland.

The monks who compiled these manuscripts were acutely aware of the spiritual and cultural stakes involved. On the one hand, they sought to immortalize the vibrant traditions of their ancestors; on the other, they were mindful of their responsibilities as Christian custodians of knowledge. In this way, they acted as cultural intermediaries, bridging the gap between the pagan and Christian traditions of Ireland.

The Fenian Cycle and Oral Poetry

The Fenian Cycle, which focuses on the adventures of Finn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna, has a particularly strong connection to the oral tradition and the art of poetry. Unlike the Ulster Cycle, which is preserved primarily in prose, the Fenian Cycle is often told in verse, reflecting its origins in the bardic tradition of the filí.

The stories of Finn and his warriors were popular among the Gaelic-speaking population of Ireland and Scotland well into the early modern period, and they were preserved not only in manuscripts like the Yellow Book of Lecan but also in folk tradition. Many of the tales from the Fenian Cycle continued to be performed by storytellers and were eventually collected by folklorists in the 18th and 19th centuries, demonstrating the enduring appeal of these heroic narratives.

The verse form of the Fenian Cycle allowed for greater flexibility in storytelling, as the poetic structure made it easier for bards to adapt the stories to suit different audiences and contexts. This adaptability helped ensure that the tales of Finn and the Fianna remained a vital part of Irish cultural identity long after they were first composed. The verse structure was also key in maintaining the integrity of the stories, as the formal constraints helped to preserve narrative elements even as details changed with each telling.

The Mythological Cycle and the Lebor Gabála Érenn

The Mythological Cycle is concerned with the early history of Ireland and the mythical beings who inhabited the island before the arrival of the Gaels. Central to this cycle is the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of Invasions), which provides a pseudo-historical account of the successive invasions and settlements of Ireland.

The Lebor Gabála Érenn was compiled in the 11th century, drawing on both oral tradition and earlier written sources. It presents the mythological history of Ireland as a series of invasions by different groups, including the Partholonians, the Nemedians, the Fir Bolg, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and finally the Milesians, who are portrayed as the ancestors of the Irish people. The Tuatha Dé Danann, often described as gods or supernatural beings, are central figures in the Mythological Cycle, and their stories form the foundation of much of Irish mythology.

The Lebor Gabála Érenn is an example of how Irish scribes sought to reconcile their pagan heritage with their Christian faith. The text portrays the history of Ireland as part of a divine plan, with each successive invasion representing a stage in the island’s development. The Tuatha Dé Danann, for example, are depicted as skilled in magic and deeply connected to the land, but their ultimate defeat by the Milesians is presented as part of the progression toward the Christian present.

The Lebor Gabála Érenn is an important source not only for its mythological content but also for its role in shaping the way the Irish understood their history. By framing the mythological past as a precursor to the Christian present, the scribes who compiled the Lebor Gabála Érenn helped to create a sense of continuity between the pagan and Christian eras of Irish history. The narrative of invasion, displacement, and divine intervention became a model that reinforced the Christian worldview while honoring Ireland’s legendary past.

The Historical Cycle: Kings and Legends

The Historical Cycle, or Cycle of the Kings, is somewhat distinct from the other mythological cycles in that it deals primarily with semi-historical figures—kings and heroes whose exploits are rooted in history but are embellished with mythic elements. These stories were preserved in manuscripts such as the Book of Leinster and the Annals of the Four Masters, which provide accounts of the reigns of various Irish kings, their battles, and their alliances.

The Historical Cycle includes tales of figures such as Cormac mac Airt, Niall of the Nine Hostages, and Conaire Mór, whose reigns are described in ways that blur the line between history and mythology. These stories often served a political purpose, as they were used to legitimize the claims of certain dynasties by linking them to heroic ancestors and the divine right to rule.

The Annals of the Four Masters, compiled in the 17th century by the Franciscan friar Mícheál Ó Cléirigh and his collaborators, is a key source for understanding the Historical Cycle. The Annals sought to provide a comprehensive history of Ireland from the earliest times to the 17th century, and they drew heavily on earlier manuscripts and oral tradition. While the Annals are often considered a historical text, they include numerous mythological elements, particularly in their accounts of the early kings of Ireland.

The Historical Cycle also played an important cultural role in preserving a sense of Irish identity during times of political upheaval. By linking contemporary rulers to heroic ancestors, these stories served as a source of inspiration and legitimacy, reinforcing the idea of continuity in Irish leadership and culture. This was particularly important during periods when native Irish rule was challenged by external forces, as the Historical Cycle provided a mythic foundation for the endurance and resilience of Irish sovereignty.

The Role of Scribes and Monasteries

The preservation of Irish mythology in medieval manuscripts is largely due to the efforts of scribes working in monastic scriptoria. These monks were scholars who dedicated themselves to preserving not only the religious texts of Christianity but also the cultural heritage of Ireland. The monasteries of Clonmacnoise, Terryglass, and others were major centers of learning, where the work of transcribing and compiling texts was carried out with great care and reverence.

The scribes who preserved Irish mythology were working at a time when Ireland was undergoing significant cultural change. The spread of Christianity had brought new ideas and values to the island, and the monasteries were the centers of this new faith. However, the monks also recognized the importance of the pre-Christian heritage of Ireland, and they sought to preserve it even as they reinterpreted it in light of their new beliefs.

This dual role of the scribes—as both preservers of the past and agents of cultural change—resulted in the unique blend of pagan and Christian elements that characterizes Irish mythology as it has come down to us. The manuscripts they produced are not simply records of ancient stories; they are also reflections of the cultural and religious tensions of their time.

Moreover, the monasteries served as hubs of cultural interaction. Irish monks traveled throughout Europe, establishing connections with other centers of learning and bringing back influences that enriched their own traditions. The presence of Latin, alongside Old and Middle Irish, in the manuscripts demonstrates the breadth of the scribes’ education and the eclectic nature of their intellectual pursuits. The cultural output of these monasteries, therefore, represents a fusion of native Irish traditions with broader Christian and European influences, creating a uniquely Irish literary canon.

The sources of Irish mythology are a rich tapestry woven from oral tradition, medieval manuscripts, and the dedicated efforts of scribes who sought to preserve the cultural heritage of Ireland. The Book of the Dun Cow, the Book of Leinster, the Yellow Book of Lecan, the Great Book of Lecan, and the Book of Ballymote are among the most important written sources, each offering a unique window into the myths, legends, and cultural values of early Ireland.

The work of the filí, the bards and poets who preserved these stories through oral tradition, was foundational to the development of Irish mythology. The scribes who eventually wrote down these stories were faced with the challenge of reconciling the pagan past with the Christian present, and their work reflects the complexity of this task. The manuscripts they produced are not only records of mythology but also artifacts of a culture in transition.

Irish mythology, as preserved in these manuscripts, is a testament to the resilience of a people and their stories. It speaks to the enduring power of myth to shape identity, convey values, and connect us to our past. Through the efforts of the storytellers, scribes, and scholars who preserved these tales, the myths of ancient Ireland continue to captivate and inspire, offering a glimpse into a world of heroes, gods, and the timeless struggle between light and darkness.

The integration of these stories into the manuscripts of medieval Ireland ensured that they survived through centuries of cultural upheaval and change. They have provided a foundation upon which the Irish cultural identity has been built, giving voice to themes of heroism, sacrifice, loyalty, and the enduring connection to the land. The manuscripts are not merely collections of stories; they are records of a cultural journey—an enduring link between Ireland's ancient past and its present, ensuring that the voices of its heroes and the echoes of its myths will never be forgotten.